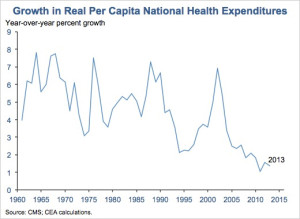

In 2013, the rate of health care spending grew at its lowest rate since 1960, which was when the federal government first began tracking it. Health care spending added up to $2.9 trillion in 2013, a 3.6 percent increase, or $9,255 per person, from 2012. The next lowest increase was 3.8 percent in 2009, as published in the report in the journal Health Affairs. Those rates fall within the range of recent low annual growth rates in health care spending, between 3.6 and 4.1 percent from 2009 to 2013. Spending on health care grew at a similar pace as the economy and reflected 17.4 percent of the gross domestic product, which accounts for the total output of goods and services.

The Obama administration suggests that limits on Medicare payments to hospitals and health maintenance organizations, cuts in federal spending, and the prevalence of high-deductible health insurance plans have contributed to discouraging the use of care by requiring consumers to pay more health costs, and in turn have controlled the growth of health care spending. However, quicker growth in Medicaid spending offset some of the restraint on Medicare and private insurance spending. The 2013 statistics did not include the effects of Medicaid expansions that were implemented this year.

The figures did not answer the question debated by health policy experts: whether the recession or the Affordable Care Act had a hand in the slowdown in health care spending. The writers of the report asserted that some provisions of the Act “exerted downward pressure” on health spending, while others “exerted upward pressure.” The report suggests that the key question is whether the growth will accelerate once the economy significantly improves; it is speculated that it will due to historical evidence.

A factor that may have contributed to the slower rate of increase is the retail market of prescription drugs, which amounted to $271 billion in 2013. This accounted for 9.3 percent of all health spending. This share of health care spending has not increased significantly recently, due to an increase in use of high-cost specialty medicines and a greater use of low-cost generic drugs.

Additionally, the Affordable Care Act requires federal and state officials to review insurance rates to identify “unreasonable increases in premiums,” and requires insurers to spend at least 80 percent of premium revenue on health care. The report stated that these provisions contributed to controlling health spending. Further, the government stated that inpatient and outpatient hospital services were used less in 2013, overlapping with requirements for patients to share more of the cost under some types of insurance.

In conclusion, the report asserted that medical prices increased 1.3 percent last year, which was marginally less than prices in the general economy. Medical price growth is calculated using the chain-weighted national health expenditures (NHE) deflator for NHE. Prices for doctors’ services increased less than one-tenth of 1 percent, which amounted for the smallest change since 2002. Prices for home health care services also declined. Medicare spending for doctors’ services increased 2.5 percent, while Medicaid spending for these services increased 14.9 percent, essentially because of a short-term increase in payment rates for primary care physicians who were treating Medicaid beneficiaries. Medicare and Medicaid accounted for more than one-third of all health spending.

The government should continue to impose limits on health spending through different areas of health care to sustain the growth of health spending in the United States, especially while the general economy has yet to recover. It is important for the government to use its resources wisely when deciding where to allocate them. As health advocates and the general public realize, it is essential to find a balance between providing high quality medical care while controlling health spending relevant to the general economy.